BATEK BUTBUT

THE VANISHING SKIN ART OF THE KALINGAS

Introduction

In the 1930's Spanish photographer Eduardo Masferre came upon a tribe in the highlands of Bugnay, Tinglayan, Kalinga, whom he heard had perfected the art of body tattooing. He immortalized this little known tribe in an anthology of black and white photographs, all capturing the people's day-to-day activities. It took Masferre two decades to finish his book.

Seventy five years later, Filipino photographer Bahaghari set out to continue where Masferre left off, using his lens to document the life and times of the tribe whose culture and tradition are being threatened by modern living.

Since that first trip in 2003, Bahaghari has gone back several times to document the Kalinga way of life. For Bahaghari, the project is an ongoing process of discovery. And in that process, he has accumulated photographs that particularly documented the indigenous yet vanishing skin art of the Kalingas.

The Kalinga

The Kalingas are the home-grown peoples of Kalinga. Of mixed Malay and Negrito origin, the Kalinga is surprisingly tall, with straight hair, high cheekbones and eyes that, though shaped like the Chinese, are set level and often far apart. (Maramba, 1998) They are generally known to be tall, dark complexioned, and lissome with high bridged noses. Physically they are very sturdy and well-built so that their war-like characteristics make them more like soldiers. (National Commission on Indigenous Peoples) Being extremely well-formed – finer of bone and muscle than their neighbor, the Bontoc, “the typical Kalinga warrior is said to be the finest looking wild man to be found in the Philippines” (Worcester, 1911)

The name Kalinga is believed to have come from Ibanas Kalinga and Gaddang Kalinga which both mean "headhunters." The Kalingas must have acquired their name because of their tradition of headhunting during tribal wars. (The Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines, Rex Book Store, 2000)

They inhabit Kalinga, a province that bears their tribal name in an area that extends from the western crests to the eastern lower flanks of the Cordillera Central in northern Luzon. This rugged landscape, though less precipitous than that of the Bontoc Igorots and Ifugaos, is still high – at 2,000 feet on the average. (Maramba, 1998)

The Kalingas settle on leveled or terraced areas on the slopes of steep mountains near rivers and streams with free, clear running water through the Chico, Pasil, Tanudan Rivers with wide plateaus and floodplains and a large portion of open grass lands. (The Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines, Rex Book Store, 2000)

The Ngibat Village

Tinglayan is a 5th class municipality in the province of Kalinga, Philippines. According to the 2000 census, it has a population of 14,164 people in 2,550 households. Tinglayan is politically subdivided into 20 barangays; of which Ngibat is one of the barangays. (Wikipedia)

Ngibat is a village situated in the southernmost tip of Tinglayan town in Kalinga. It is inhabited by the Butbut tribe, one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera Region. It was known as Masinta in the earlier period. From Bontoc proper, it takes two-and-half hours ride by jeep along the Bontoc - Kalinga National Road to Barangay Maswa, which is the nearest entry point to the village. It is accessible by foot from Maswa roadside, along trails passing through vast cogon land, the Micro-hydro Project of the Montañosa Research and Development Center (MRDC), and several rice fields. Ngibat is accessed from Tinglayan through Tulgao East which is partly concreted by the municipal government of Tinglayan. (Puerto, Nordis Weekly, 2005)

The Spendor Of Tattoos

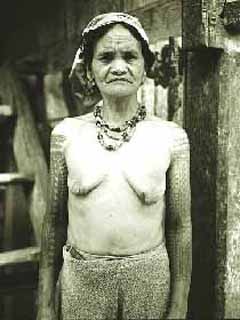

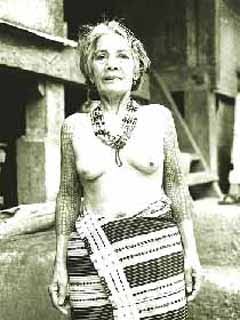

Tattoos were symbols of male valor: They were applied only after a man had performed in battle with fitting courage, like modern military decorations they accumulated with additional feats. Headhunting was the only reason or purpose for tattooing. From years of research, the process of tattooing are known, the deeper role and function of tattoos are revealed together with their symbols and meanings in their proper context and historical symbolism. Although it became a lost visage in the following century, the tattoos are for complex rites of passage, tribal identity, prestige, power, healing, protection, beauty and reason. (Salvador, 2004)

Caroline Kennedy-Cabrera, in her work among the tribal communities in northern Luzon, believed that women underwent tattooing on their legs, arms, and breasts to enhance their beauty. The men, on the other hand, did so to mark age, bravery, and tribal seniority. In some tribal communities, it was claimed that tattoos had magical qualities; thus, designs of scorpions, centipedes, snakes, and bats were often repeated. (Casal, et. al.)

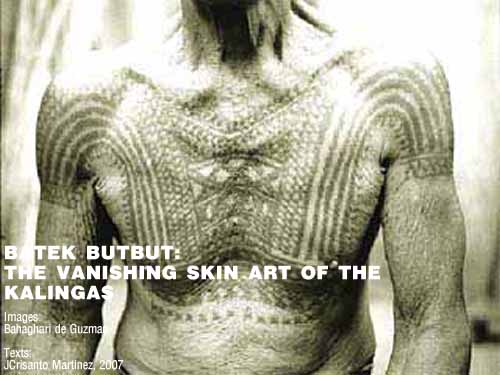

The Kalinga men, in general, used only armlets and necklaces as ornaments, but their chests, backs, arms, and faces were covered with elaborate and beautiful tattoos. This was true mostly of the men of south Kalinga, as they wore no upper garments. The tattooing imitated the upper garment worn by the men of north Kalinga called silup, reproducing the silup's designs on the arms and shoulders. (Casal, et. al.)

They tattoo their arms, chest, upper parts of the backs, and faces with intricate designs. Sets of three to five lines radiate from the waist and curve outward to the chest round the collar bone down the arms all the way to the hands. The design has a cell-like structure or net pattern which has also been described as reminiscent of “fish scales.” (Roces, 1991) Stripes of a centipede-leg have been described as a “fern leaf or feather pattern. (Schadenberg, 1888) Scars are usually surrounded with tattoos of radiating lines. (Meyer) The instrument for tattooing was a piece of carabao horn bent at right angles. Its shorter end was furnished with sharp pieces of wire. These needles were positioned against the skin and driven in by a stoke from a wooden hammer. After 20 strokes, the wound was vigorously rubbed with soot obtained by burning resinous wood. A pot held over the flames collected the soot. (Maramba, 1998) For the South Kalinga, tattoos held headhunting significance and must be viewed in the context of the “cult of the warrior.” (Roces, 1991)

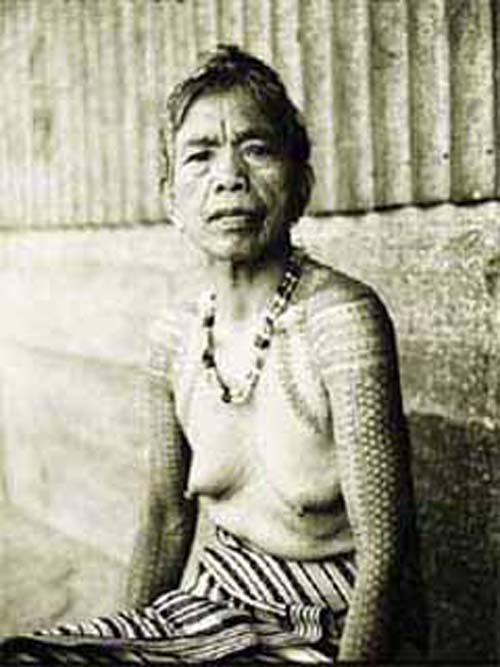

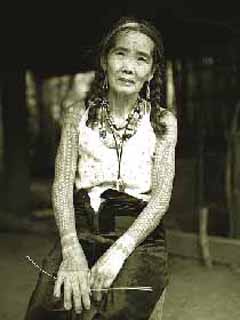

The women of south Kalinga painted their faces a bright red and wore necklaces dangling down over their breasts to their navels. Sometimes these necklaces were worn diagonally across the body, over the left shoulder and under the right armpit, like a sash. Their arms were tattooed more ornately than the arms of the Kankanay, lbaloi, Ifugao, and Igorot women. (Casal, et. al.)

Tattooing for the South Kalinga group is always in connection with headhunting. For the women, it was an honor to share in a family member’s glory. The wearing of tattoos declared this and it had the added benefit of completing her costume. Females had the right to wear tattoos if they were related to the one who had participated in a raid. Because this kinship circles are so large (relatives from the second degrees are considered “family”), almost every female could claim her right to wear tattoos. (Maramba, 1998)

Batek Butbut

In the early years, young men and women in the Cordillera were usually tattooed by an elder who occupied a high position in the community. The men who returned from war with their enemy's head, however, were allowed to get their tattoos by a maingal (warrior). The women would mostly get their tattoos at a young age to make them more attractive, while the men saw tattoos as a mark of manhood. (Salvador, 2000)

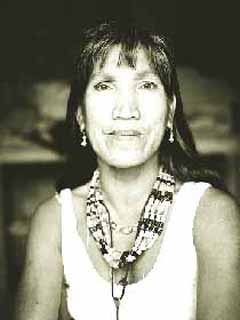

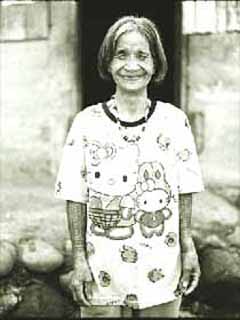

To the Kalinga, tattoos are not just skin drawings. They are testaments to the culture and they bear with them vivid commentaries and anecdotes of life in the old days which is now lost in a fast changing world. “In Kalinga, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, a government agency tasked to attend to indigenous people’s concerns, has listed tattoos as cultural and heritage treasures, and recently, it documented the last carriers of this lost tradition in photographs and narratives. The aging bodies of the men and women of Kalinga are the canvasses of the vanishing art of body tattooing in the Cordillera. Around 50 of them still alive today carry the mobile art of a bygone era, and only one tattoo artist remains in the villages of Tinglayan and Tanudan in Kalinga.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

Tattoos have also been viewed as heirlooms. “Among the illustrated Kalingas are 46 women who say that if they had a choice some 50 years ago, they would not have consented to undergo the pain of tattooing. At the urging of their parents and their elders, they agreed back then to have their bodies tattooed because of the belief that a person with no tattoos was no good. “Madi ti awan batek na. Nu matay ka isu ti tawid mi nga matay. Issu la ti maitugut mi (It was taboo then to be without tattoos. The tattoo is the only thing that you can bring with you into the next life),” says Josephine Apayao, 60 years old. (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Batek is the ethnic word for tattoo in some parts of the Cordillera, and the mambatek is the old man who is the artist and executioner of his own designs. Batek is also the word for the antique beads such as the colorful chevrons, agates, corals, and sometimes bones, worn as adornment by the ethnic tribes.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Here, only the landed rich known as baknangs, who owned precious beads to give their children as inheritance, could have the tattoos that went with wearing the beads. Sometimes the tattoos mimicked the designs of the beads. Because they had the means, the baknangs could afford the time to go through the process of tattooing, which meant having fewer field hands for weeks until they regained the strength from the agony of being tattooed.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Most of the Kalinga women had their tattoos at age 16. Parents made their daughters undergo tattooing as early as 12 years old. But tattoos were important in finding a mate because in their day, a woman without tattoos was unattractive in the eyes of the men.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“The resinous branch of a pine tree was burned and pounded into a fine powdery consistency in a clay pot, then transferred into a bowl where the juice of sugarcane was poured. The mixture was made into small balls and dried under the sun.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

Naty Sugguiyao, chief of the NCIP-Kalinga explained that there were more women than men with tattoos because while tattoos were worn by the women for adornment, the men had to earn their bateks. Thus, they got their tattoos at a later age. Batek for the men was like a star or a medal of bravery in battle. It signified a kill or the head of an enemy taken in the fierce tradition of kayaw (headhunting). It was taboo or mabarros (a curse) for a man to have a tattoo for no reason. The common tattoo designs include the ‘binatbattoko’ design on the arms and the ‘inadi-adik’ or a rounded design on the chest. Other tattoo designs documented were the ginaygayaman (centipede), linalfalafat (from a flower called ‘lafat’), uleg (snake), inulufug, inaki-akit (a design copied from the rattan fruit skin).” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

A lost tradition Iking Salvador, a young anthropologist and a faculty member of the University of the Philippines College Baguio did a thesis on the tattoo tradition of Kalinga, particularly in Lubo which concluded that the art of tattooing is now a lost tradition in Kalinga. Their tattoos are now chronicles of a unique era in their culture.

Conclusion

In the early years, young men and women in the Cordillera were usually tattooed by an elder who occupied a high position in the community. The men who returned from war with their enemy's head, however, were allowed to get their tattoos by a maingal (warrior). The women would mostly get their tattoos at a young age to make them more attractive, while the men saw tattoos as a mark of manhood. (Salvador,)

The Kalingas wore batek in the past because of the scarcity of clothing. But now, with the abundance of clothing, tattooing has lost its necessity for the younger generation. There has been no transfer of this knowledge to the younger generation. The old mambateks have died.

The bodong is the most admirable and efficient Kalinga institution. It is a peace pact or treaty between two tribes, wherein the Pagta or laws on inter-tribal relations are made. The bodong is also the Magna Carta of the Kalingas. Thus, with the absence of tribal wars, headhunting is no longer practiced. And the young Kalingans are not even interested in this old tradition, as shown by their refusal to have tattoos. It is a lost tradition. And the last generation of tattooed people in the Kalingas who are mobile testaments of the Cordillera culture have aged, their skin art left only to be documented.

The Ullalim Festival is an annual celebration of the province’s founding anniversary after its separation from Apayao province on Febuary 14, 1995. The festivities marking the creation of Kalinga as a separate province feature the songs, dances and exhibits about the life of the Kalingas. It is also one rare opportunity for the generation of tattooed people in the Kalingas to parade with pride the archives of a unique era in their culture; the batek.

With the full enforcement of the bodong, and headhunting no longer practiced, modern education and concepts of decoration contributed to the fading out of the practice of tattooing. Beauty has come to be defined not in terms of body tattoos, but through commercial beauty aids. The only testimony now to the practice of the art of batek is the few remaining living elders who have various bodily tattoos. With their deaths, this ancient practice shall be buried with them, unless the new generation starts to appreciate and continue to share the tradition.

Images:

Bahaghari de Guzman

Texts:

JCrisanto Martinez, 2007

Bibliography

Addamo, Narciso S. & Allad-iw, Arthur L. (8 Oct 2006). Tattooing: A vanished art among the I-Kalinga? Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.nordis.net/blog/?p=208

Casal, Fr. Gabriel S. Dizon, Eusebio Z. & Ronquillo, Wilfredo P. (n.d.). Pintados. Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People Vol. 2.

Maramba, Roberto. (1998). Form and splendor: Personal adornment of northern Luzon ethnic groups, Philippines, Makati City: Bookmark.

National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. (n.d.). Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.ncip.gov.ph/resources/ethno_detail.php?ethnoid=63

Puerto, Francie. ( August 7, 2005). Indigenous rice farming in Kalinga. Nordis Weekly. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.nordis.net/news/2005/ndw050807/ndw050807_05indigi-rice.htm

Roces, Marian Pastor. (1991). Sinaunang habi: Philippine ancestral weave. Manila: The Nikki Coseteng Filipiniana Series.

Salvador, Ikin. (May 2, 2000). Cordillera’s vanishing art of tattooing. Philippine Daily Inquirer Internet Edition. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.seasite.niu.edu/Tagalog/Tagalog_Default_files/Philippine_Culture/Regional%20Cultures/northern_luzon_cultures.htm

Salvador,Ikin. (November 3 – 14, 2004). Signs on skin, beauty and being: Traditional tattoos and tooth blackening among the Philippine Cordillera. An exhibition of photographs and artifacts. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.orpilla.com/Tattoo.html

Tabuk, Kalinga. (n.d.). Retrieved February 01, 2007, from www.myspace.com-batik

Wikipedia (n.d.). Kalinga. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinglayan%2C_Kalinga

Worcester, Dean C. (September, 1912). Field sports among the wild men of northern Luzon. National Geographic Vol. 22 No. 3 Washington D.C.

THE VANISHING SKIN ART OF THE KALINGAS

Introduction

In the 1930's Spanish photographer Eduardo Masferre came upon a tribe in the highlands of Bugnay, Tinglayan, Kalinga, whom he heard had perfected the art of body tattooing. He immortalized this little known tribe in an anthology of black and white photographs, all capturing the people's day-to-day activities. It took Masferre two decades to finish his book.

Seventy five years later, Filipino photographer Bahaghari set out to continue where Masferre left off, using his lens to document the life and times of the tribe whose culture and tradition are being threatened by modern living.

Since that first trip in 2003, Bahaghari has gone back several times to document the Kalinga way of life. For Bahaghari, the project is an ongoing process of discovery. And in that process, he has accumulated photographs that particularly documented the indigenous yet vanishing skin art of the Kalingas.

The Kalinga

The Kalingas are the home-grown peoples of Kalinga. Of mixed Malay and Negrito origin, the Kalinga is surprisingly tall, with straight hair, high cheekbones and eyes that, though shaped like the Chinese, are set level and often far apart. (Maramba, 1998) They are generally known to be tall, dark complexioned, and lissome with high bridged noses. Physically they are very sturdy and well-built so that their war-like characteristics make them more like soldiers. (National Commission on Indigenous Peoples) Being extremely well-formed – finer of bone and muscle than their neighbor, the Bontoc, “the typical Kalinga warrior is said to be the finest looking wild man to be found in the Philippines” (Worcester, 1911)

The name Kalinga is believed to have come from Ibanas Kalinga and Gaddang Kalinga which both mean "headhunters." The Kalingas must have acquired their name because of their tradition of headhunting during tribal wars. (The Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines, Rex Book Store, 2000)

They inhabit Kalinga, a province that bears their tribal name in an area that extends from the western crests to the eastern lower flanks of the Cordillera Central in northern Luzon. This rugged landscape, though less precipitous than that of the Bontoc Igorots and Ifugaos, is still high – at 2,000 feet on the average. (Maramba, 1998)

The Kalingas settle on leveled or terraced areas on the slopes of steep mountains near rivers and streams with free, clear running water through the Chico, Pasil, Tanudan Rivers with wide plateaus and floodplains and a large portion of open grass lands. (The Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines, Rex Book Store, 2000)

The Ngibat Village

Tinglayan is a 5th class municipality in the province of Kalinga, Philippines. According to the 2000 census, it has a population of 14,164 people in 2,550 households. Tinglayan is politically subdivided into 20 barangays; of which Ngibat is one of the barangays. (Wikipedia)

Ngibat is a village situated in the southernmost tip of Tinglayan town in Kalinga. It is inhabited by the Butbut tribe, one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera Region. It was known as Masinta in the earlier period. From Bontoc proper, it takes two-and-half hours ride by jeep along the Bontoc - Kalinga National Road to Barangay Maswa, which is the nearest entry point to the village. It is accessible by foot from Maswa roadside, along trails passing through vast cogon land, the Micro-hydro Project of the Montañosa Research and Development Center (MRDC), and several rice fields. Ngibat is accessed from Tinglayan through Tulgao East which is partly concreted by the municipal government of Tinglayan. (Puerto, Nordis Weekly, 2005)

The Spendor Of Tattoos

Tattoos were symbols of male valor: They were applied only after a man had performed in battle with fitting courage, like modern military decorations they accumulated with additional feats. Headhunting was the only reason or purpose for tattooing. From years of research, the process of tattooing are known, the deeper role and function of tattoos are revealed together with their symbols and meanings in their proper context and historical symbolism. Although it became a lost visage in the following century, the tattoos are for complex rites of passage, tribal identity, prestige, power, healing, protection, beauty and reason. (Salvador, 2004)

Caroline Kennedy-Cabrera, in her work among the tribal communities in northern Luzon, believed that women underwent tattooing on their legs, arms, and breasts to enhance their beauty. The men, on the other hand, did so to mark age, bravery, and tribal seniority. In some tribal communities, it was claimed that tattoos had magical qualities; thus, designs of scorpions, centipedes, snakes, and bats were often repeated. (Casal, et. al.)

The Kalinga men, in general, used only armlets and necklaces as ornaments, but their chests, backs, arms, and faces were covered with elaborate and beautiful tattoos. This was true mostly of the men of south Kalinga, as they wore no upper garments. The tattooing imitated the upper garment worn by the men of north Kalinga called silup, reproducing the silup's designs on the arms and shoulders. (Casal, et. al.)

They tattoo their arms, chest, upper parts of the backs, and faces with intricate designs. Sets of three to five lines radiate from the waist and curve outward to the chest round the collar bone down the arms all the way to the hands. The design has a cell-like structure or net pattern which has also been described as reminiscent of “fish scales.” (Roces, 1991) Stripes of a centipede-leg have been described as a “fern leaf or feather pattern. (Schadenberg, 1888) Scars are usually surrounded with tattoos of radiating lines. (Meyer) The instrument for tattooing was a piece of carabao horn bent at right angles. Its shorter end was furnished with sharp pieces of wire. These needles were positioned against the skin and driven in by a stoke from a wooden hammer. After 20 strokes, the wound was vigorously rubbed with soot obtained by burning resinous wood. A pot held over the flames collected the soot. (Maramba, 1998) For the South Kalinga, tattoos held headhunting significance and must be viewed in the context of the “cult of the warrior.” (Roces, 1991)

The women of south Kalinga painted their faces a bright red and wore necklaces dangling down over their breasts to their navels. Sometimes these necklaces were worn diagonally across the body, over the left shoulder and under the right armpit, like a sash. Their arms were tattooed more ornately than the arms of the Kankanay, lbaloi, Ifugao, and Igorot women. (Casal, et. al.)

Tattooing for the South Kalinga group is always in connection with headhunting. For the women, it was an honor to share in a family member’s glory. The wearing of tattoos declared this and it had the added benefit of completing her costume. Females had the right to wear tattoos if they were related to the one who had participated in a raid. Because this kinship circles are so large (relatives from the second degrees are considered “family”), almost every female could claim her right to wear tattoos. (Maramba, 1998)

Batek Butbut

In the early years, young men and women in the Cordillera were usually tattooed by an elder who occupied a high position in the community. The men who returned from war with their enemy's head, however, were allowed to get their tattoos by a maingal (warrior). The women would mostly get their tattoos at a young age to make them more attractive, while the men saw tattoos as a mark of manhood. (Salvador, 2000)

To the Kalinga, tattoos are not just skin drawings. They are testaments to the culture and they bear with them vivid commentaries and anecdotes of life in the old days which is now lost in a fast changing world. “In Kalinga, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, a government agency tasked to attend to indigenous people’s concerns, has listed tattoos as cultural and heritage treasures, and recently, it documented the last carriers of this lost tradition in photographs and narratives. The aging bodies of the men and women of Kalinga are the canvasses of the vanishing art of body tattooing in the Cordillera. Around 50 of them still alive today carry the mobile art of a bygone era, and only one tattoo artist remains in the villages of Tinglayan and Tanudan in Kalinga.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

Tattoos have also been viewed as heirlooms. “Among the illustrated Kalingas are 46 women who say that if they had a choice some 50 years ago, they would not have consented to undergo the pain of tattooing. At the urging of their parents and their elders, they agreed back then to have their bodies tattooed because of the belief that a person with no tattoos was no good. “Madi ti awan batek na. Nu matay ka isu ti tawid mi nga matay. Issu la ti maitugut mi (It was taboo then to be without tattoos. The tattoo is the only thing that you can bring with you into the next life),” says Josephine Apayao, 60 years old. (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Batek is the ethnic word for tattoo in some parts of the Cordillera, and the mambatek is the old man who is the artist and executioner of his own designs. Batek is also the word for the antique beads such as the colorful chevrons, agates, corals, and sometimes bones, worn as adornment by the ethnic tribes.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Here, only the landed rich known as baknangs, who owned precious beads to give their children as inheritance, could have the tattoos that went with wearing the beads. Sometimes the tattoos mimicked the designs of the beads. Because they had the means, the baknangs could afford the time to go through the process of tattooing, which meant having fewer field hands for weeks until they regained the strength from the agony of being tattooed.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“Most of the Kalinga women had their tattoos at age 16. Parents made their daughters undergo tattooing as early as 12 years old. But tattoos were important in finding a mate because in their day, a woman without tattoos was unattractive in the eyes of the men.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

“The resinous branch of a pine tree was burned and pounded into a fine powdery consistency in a clay pot, then transferred into a bowl where the juice of sugarcane was poured. The mixture was made into small balls and dried under the sun.” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

Naty Sugguiyao, chief of the NCIP-Kalinga explained that there were more women than men with tattoos because while tattoos were worn by the women for adornment, the men had to earn their bateks. Thus, they got their tattoos at a later age. Batek for the men was like a star or a medal of bravery in battle. It signified a kill or the head of an enemy taken in the fierce tradition of kayaw (headhunting). It was taboo or mabarros (a curse) for a man to have a tattoo for no reason. The common tattoo designs include the ‘binatbattoko’ design on the arms and the ‘inadi-adik’ or a rounded design on the chest. Other tattoo designs documented were the ginaygayaman (centipede), linalfalafat (from a flower called ‘lafat’), uleg (snake), inulufug, inaki-akit (a design copied from the rattan fruit skin).” (Author unknown, www.myspace.com-batik)

A lost tradition Iking Salvador, a young anthropologist and a faculty member of the University of the Philippines College Baguio did a thesis on the tattoo tradition of Kalinga, particularly in Lubo which concluded that the art of tattooing is now a lost tradition in Kalinga. Their tattoos are now chronicles of a unique era in their culture.

Conclusion

In the early years, young men and women in the Cordillera were usually tattooed by an elder who occupied a high position in the community. The men who returned from war with their enemy's head, however, were allowed to get their tattoos by a maingal (warrior). The women would mostly get their tattoos at a young age to make them more attractive, while the men saw tattoos as a mark of manhood. (Salvador,)

The Kalingas wore batek in the past because of the scarcity of clothing. But now, with the abundance of clothing, tattooing has lost its necessity for the younger generation. There has been no transfer of this knowledge to the younger generation. The old mambateks have died.

The bodong is the most admirable and efficient Kalinga institution. It is a peace pact or treaty between two tribes, wherein the Pagta or laws on inter-tribal relations are made. The bodong is also the Magna Carta of the Kalingas. Thus, with the absence of tribal wars, headhunting is no longer practiced. And the young Kalingans are not even interested in this old tradition, as shown by their refusal to have tattoos. It is a lost tradition. And the last generation of tattooed people in the Kalingas who are mobile testaments of the Cordillera culture have aged, their skin art left only to be documented.

The Ullalim Festival is an annual celebration of the province’s founding anniversary after its separation from Apayao province on Febuary 14, 1995. The festivities marking the creation of Kalinga as a separate province feature the songs, dances and exhibits about the life of the Kalingas. It is also one rare opportunity for the generation of tattooed people in the Kalingas to parade with pride the archives of a unique era in their culture; the batek.

With the full enforcement of the bodong, and headhunting no longer practiced, modern education and concepts of decoration contributed to the fading out of the practice of tattooing. Beauty has come to be defined not in terms of body tattoos, but through commercial beauty aids. The only testimony now to the practice of the art of batek is the few remaining living elders who have various bodily tattoos. With their deaths, this ancient practice shall be buried with them, unless the new generation starts to appreciate and continue to share the tradition.

Images:

Bahaghari de Guzman

Texts:

JCrisanto Martinez, 2007

Bibliography

Addamo, Narciso S. & Allad-iw, Arthur L. (8 Oct 2006). Tattooing: A vanished art among the I-Kalinga? Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.nordis.net/blog/?p=208

Casal, Fr. Gabriel S. Dizon, Eusebio Z. & Ronquillo, Wilfredo P. (n.d.). Pintados. Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People Vol. 2.

Maramba, Roberto. (1998). Form and splendor: Personal adornment of northern Luzon ethnic groups, Philippines, Makati City: Bookmark.

National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. (n.d.). Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.ncip.gov.ph/resources/ethno_detail.php?ethnoid=63

Puerto, Francie. ( August 7, 2005). Indigenous rice farming in Kalinga. Nordis Weekly. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.nordis.net/news/2005/ndw050807/ndw050807_05indigi-rice.htm

Roces, Marian Pastor. (1991). Sinaunang habi: Philippine ancestral weave. Manila: The Nikki Coseteng Filipiniana Series.

Salvador, Ikin. (May 2, 2000). Cordillera’s vanishing art of tattooing. Philippine Daily Inquirer Internet Edition. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.seasite.niu.edu/Tagalog/Tagalog_Default_files/Philippine_Culture/Regional%20Cultures/northern_luzon_cultures.htm

Salvador,Ikin. (November 3 – 14, 2004). Signs on skin, beauty and being: Traditional tattoos and tooth blackening among the Philippine Cordillera. An exhibition of photographs and artifacts. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://www.orpilla.com/Tattoo.html

Tabuk, Kalinga. (n.d.). Retrieved February 01, 2007, from www.myspace.com-batik

Wikipedia (n.d.). Kalinga. Retrieved February 01, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinglayan%2C_Kalinga

Worcester, Dean C. (September, 1912). Field sports among the wild men of northern Luzon. National Geographic Vol. 22 No. 3 Washington D.C.